Hydatid Cysts of the Liver

In humans hydatid disease is caused by the larvae of a tapeworm called Echinococcus granulosus. This parasitic infection occurs worldwide and is endemic in some countries such as Australia and the Middle East, especially in sheep farming areas. Hydatid disease is a serious and potentially fatal condition, which may remain hidden in the body for many years.

How can humans become infected with this tapeworm?

Hydatid disease in humans is caused by contact with dog feces or dog hair infected with the tapeworm eggs, or contaminated vegetables. The eggs may stick to the animal’s hair or contaminate the vegetable garden. The eggs are highly resistant to the environment and can remain alive for months. Human infection does not occur from eating infected offal. Hydatid disease is not contagious and is not passed by person-to-person contact.

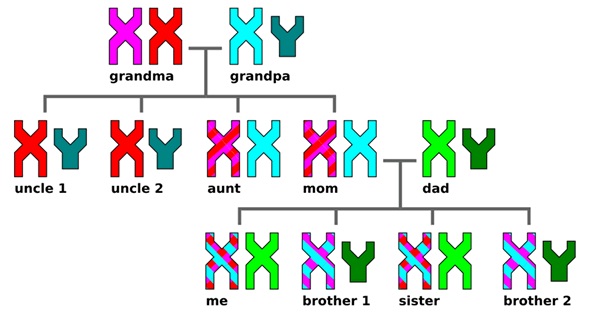

Life cycle of a tapeworm

The life cycle of the tapeworm alternates between herbivores and carnivores—(typically sheep, foxes and dogs). Humans are an accidental intermediate host and become an end point in the tapeworm’s lifecycle.

The sheep ingests the eggs which hatch in the sheep’s intestine and then travel to the liver where the hydatid cyst develops. When a dog eats the sheep’s organs containing the hydatid cyst, the dog becomes infected and passes eggs out in their feces. Cows and sheep become infected by eating the grass contaminated by dog feces. Other animals that may be infected include pigs, cattle, goats, horses, camels, wombats, wallabies and kangaroos. The grazing animal eats dog, fox or dingo feces infected with tapeworm eggs. Eventually the animal’s organs (such as the liver, brain or lungs) grow watery sacs called hydatid cysts. These cysts contain tapeworm heads and a mature cyst may contain several million such heads.

Symptoms of Hydatid Disease in Humans

The symptoms of hydatid disease vary according to which body organs are infected. The most commonly infected organ is the liver, but the brain, kidneys and lungs are sometimes affected. The slow growing cysts are localized in the liver (in 75% of cases), the lungs (in 5-15% of cases) and other organs in the body such as the spleen, brain, heart and kidneys (in 10-20% of cases). The cysts are usually filled with a clear fluid called hydatid fluid and are spherical and usually consist of one compartment.

Symptoms can occur a long time after infection and sometimes many years later, but there may be no symptoms at all. If they occur, symptoms may include:

- Weight loss

- A swollen and bloated abdomen

- Anemia

- Fatigue

- A cough – and blood or liquid from a ruptured cyst may be coughed up

- Jaundice – pressure from a growing cyst may obstruct the bile ducts

- Malnutrition – sometimes, a lack of vitamins can be caused in the host by the very high nutrient demand of the growing parasite

If the cysts were to rupture while in the body, during surgical removal of the cysts, or by some kind of trauma to the body, the patient would most likely go into a type of shock called anaphylaxis which leads to high fever, severe itching, hives, swelling (edema) of the lips and eyelids, shortness of breath, wheezing and sneezing. Hydatid disease can be fatal without emergency medical treatment.

How is Hydatid Disease Diagnosed?

By a thorough medical history and physical examination

- Imaging tests such as chest X-rays, ultrasound and CAT or MRI scans

- Examination of blood, urine, sputum and feces

- Blood tests for antibodies to the cysts

Treatment of Hydatid Disease

The standard form of treatment is surgical removal of the cysts. This is combined with drugs such as albendazole and/or mebendazole before surgery and for 8 weeks after surgery to clear up any spilled hydatid fluid containing live tapeworm components.

One of the risks is that a hydatid cyst may rupture during surgery and spread tapeworm heads throughout the patient’s body. This risk is mitigated by prescribing high doses of the drug albendazole with the surgery, which helps to destroy any remaining tapeworm heads. Unfortunately the risk of recurrence of hydatid disease is high and around 30% of patients treated for hydatid disease develop the condition again and need repeat treatment.

If there are cysts in multiple organs or tissues, or the cysts are in dangerous places in the body, surgery may be too difficult and dangerous and in these cases drugs (Albendazole or Mebendazole) and/or PAIR (puncture-aspiration-injection-reaspiration) become the only possible treatment.

PAIR is a minimally invasive procedure that uses three steps:

- Puncture and needle aspiration of the cyst

- Injection of a scolicidal solution for 20-30 minutes

- Cyst-re-aspiration and final irrigation

There is currently research into a new treatment called Percutaneous Thermal Ablation (PTA) of the germinal layer in the cyst by means of a radiofrequency ablation device. This form of treatment is still new and requires much more testing before being widely recommended.

Preventing infection with the Hydatid Tapeworm

There is a huge need for health education programs, improved water sanitation and better standards of hygiene. Humans can become infected with echinococcus eggs via touching contaminated soil, animal feces and animal hair. It is also important to intervene at certain stages of the tape worm’s life cycle, especially the infection of hosts (most commonly domestic dogs). Effective interventions include regular de-worming of dogs and vaccinating dogs and other livestock, such as sheep, that also act as hosts for the tapeworm.

Preventative suggestions include:

- Regular preventive de-worming of dogs. It is important to control tapeworm infection in domestic dogs. Infected dogs usually don’t have any symptoms and appear healthy.

- Dispose of your dog’s feces carefully and wear rubber gloves. Wash your hands thoroughly after disposing of dog droppings.

- Always wash your hands with plenty of soap and water after touching your dog. Wash hands before eating and drinking and after gardening or handling animals.

- Only feed your dog with commercially prepared dog foods.

- Never feed offal (either raw or cooked) to your dog.

- Take your dog to the vet for treatment with anti-tapeworm medication if you suspect an infection in your dog.

- If your dog has a proven infection, incinerate or bury deeply all dog feces until a cure is pronounced. Clean and disinfect the kennel and surrounding living area.

- Be especially vigilant if you are a sheep or cattle farmer and prevent your dogs from eating carcasses.

- Do not allow your dog to roam when holidaying in country areas.

- If you grow your own vegetables, fence your vegetable gardens to ensure that domestic and wild animals do not defecate on the soil.

Currently there are no human vaccines against any form of echinococcosis. However, there are studies being conducted for an effective human vaccine against echinococcosis.